One of the many privileges of living in Pakistan is enjoying its rich bird life. Due to its topographical variety Pakistan plays host to a huge range of bird varieties which migrate up and down the country. Most are easy to spot, even when you’re trying to do so while holding a toddler with one arm and attempting to stop three other children from shouting with excitement and scaring all the birds away. So without further ado, here are just some of the birds I saw last weekend in Murree…

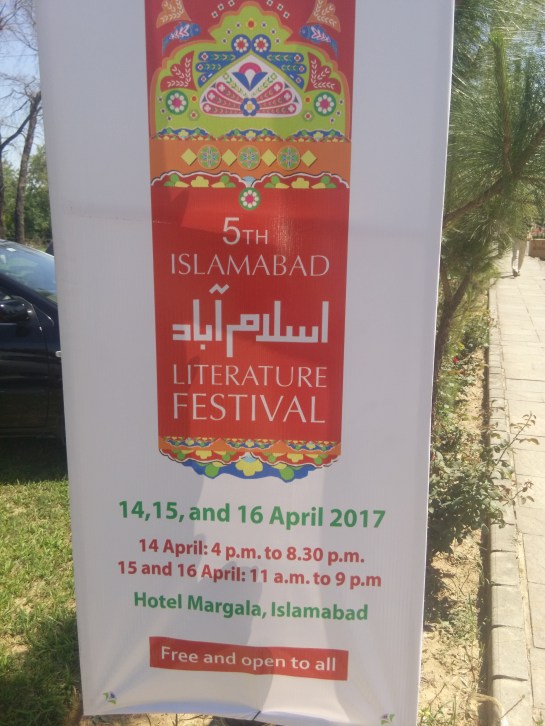

Islamabad Literary Festival: Civil Society’s Day Out

uivaLiterary festivals have become quite a South Asian phenomenon in recent years. In India they have taken off in Jaipur, Chandigarh, Delhi, Kochi, Pune, Goa and a host of other locations. In Pakistan they have been taking place in Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad for the last five years or so. The Islamabad Literary Festival 2017 took place at the Margala Hotel over the Easter weekend.

I have been attending the Lahore Literary Festival since it began, but this was my first time at its Islamabad equivalent. I find these events really heartening: it is undeniably encouraging to see thousands and thousands of people giving up their weekend to pack out a hotel in the centre of the city and listen to people giving lectures on the history of Pakistani literature in English, on Urdu poetry, or discussing recurrent themes in contemporary Pakistani literature.

Foreign observers have thankfully stopped finding this bizarre. In the early days of the Lahore Literary Festival correspondents from the UK and the US covered the event in tones of mild bemusement, employing gratuitously sensational phrases describing Lahorites dodging bombs to attend the festival. The festivals have been running for long enough now that they have become part of the social landscape, and foreigners air-dropped in to observe the event at the behest of some desk-bound editor no longer find them surprising. The sight of thousands of Pakistani people coming together to talk about books is no longer weird, as if it ever should have been.

These festivals, after all, provide an opportunity for Pakistani’s “liberal elite” to enjoy a day in the sun. I do not use that term negatively. Why should it be negative? The liberal elite of Pakistan have significant influence on society and use that influence positively and constructively. They come in their thousands to talk about poetry and novels, as well as less obviously literary topics such as Pakistan’s looming water crisis, and they clearly care. They do not come up with solutions to Pakistan’s problems – how could they, in a three-day event? – but the fact that discussions are ongoing, and passionately, is a positive start in itself.

The narrative about Pakistan is overwhelmingly negative. It is good to be able to report that thousands of people were willing to come out, discuss poems, buy novels, drink tea, and chat politely with anyone they could find. Clearly, it’s not all bad news.

Amritsar, Grace, and the Power of History

On April 13th 1919 protesters had gathered in the Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar, India. Several thousand people in all packed the public gardens. The British Army officer in charge of the city, Colonel Reginald Dyer, assembled a unit of 90 Gurka soldiers under British command and proceeded to the gardens. He ensured that the exits were blocked and ordered his troops, armed with Lee-Enfield rifles, to open fire. They continued to fire for ten minutes until their ammunition was expended.

The official death toll, according to the British, was 379 dead and over a thousand wounded. The report issued by the Indian National Congress claimed that more than a thousand had been killed. The alleyways leading to the garden were too narrow for Dyer’s armoured cars and so he had to leave them behind. At the inquiry he testified that he would have used them, and their machine guns, if he had been able to.

I visited Amritsar on my way from India to Pakistan in 2009, ninety years after the atrocity. I vividly recall visiting the Jallianwala Bagh and walking around the memorial site which felt very much like sacred ground for the Indian independence movement. Bullet holes in the walls were still visible. The well, down which many people threw themselves to avoid the bullets, is still visible. 120 bodies were later removed from its depths.

Yet the impression which is seared most powerfully onto my memory is the reception I received from Indians visiting the site. I wanted to hide away, to go incognito, to avoid being connected with the massacre. I am British, after all, and although even my grandparents were not born in 1919 I nevertheless feel a sense of regret and grief at what happened. While not personally responsible for it I am nevertheless connected, by dint of my passport if nothing else. I tried to avoid people, to avoid getting into conversations, and yet Indian people are so welcoming that this was impossible.

A group of Indian students came over to say hello. I explained what I was doing and told them about my impressions of India and of Amritsar. Eventually I couldn’t hold it in any more, and I blurted out:

“I’m so sorry for what happened here”.

The students smiled. Oh please, do not worry. It was a long time ago. These things are in the past. You should not worry about it. You are welcome. You are most welcome.

“You are most welcome in India”.

We shook hands and departed, and as I walked back to my hotel in the searing May heat my footsteps were oddly light.

A Visit to Katas Raj

At first sight the land of Pakistan is almost entirely Islamic. Its population is something like 97% Muslim, of course, and mosques are found everywhere, from rural villages to large cities. Yet a closer inspection reveals a surprising truth: that this land has a history far more diverse and complex than would first seem to be the case.

This becomes very clear when you visit the Hindu temple complex at Katas Raj, near Chakwal in the Punjab. The complex is located in the Salt Range, an immense line of mountains which separate the plains of the Punjab from the Potohar Plateau. These mountains were formed when an ancient sea, long since dry, was thrust upwards by tectonic activity. The temples are located in a fold of land in this beautiful part of the country.

Hindu teaching has it that the temples were formed from the tears of the grief-stricken Lord Shiva on the death of his wife, Sati. There are seven temples on the site, each dedicated to a particular Hindu deity, and many of them still contain original features such as carved wooden door frames or magnificent frescoes depicting scenes from Hindu mythology.

In 1947, when the tragedy of Partition tore the Punjab in half, the vast majority of Hindus left the newly-formed nation of Pakistan and migrated to India. The complex was left to deteriorate, with nobody showing an interest in its upkeep, and signs of decay are evident. The pool itself, formed from the tears of Lord Shiva, is muddy and neglected; nearby cement factories have drained much of its water and the remaining water is muddy and garbage-strewn. Yet to the credit of the Pakistani government steps are being taken to rectify this situation: many of the temples have new rooves, are newly painted, and even the damaged frescoes are being repaired.

The temple even hosts Hindu pilgrims, many of whom come from the southern province of Sindh, and some of whom even come in selected groups from India during auspicious Hindu festivals. Given the hostility between India and Pakistan and the agony of Partition, it is surprising and heartening that Katas Raj exists at all, and particularly encouraging that the Pakistani government is taking steps to restore and protect it. Long may this continue.

Migration, and the Malaysian Mega-Church

The mega-church was huge. A semi-circle of comfortable seats faced a large stage backed with three large TV screens. Cameras were positioned in the centre and on either side, relaying live images to the screens. The worship was led by a Malaysian man with several backing singers, both male and female. There were well over a thousand people in attendance, almost entirely young Malaysians.

I have an instinctive dislike for mega-churches. The kind of slick, prosperous message which they often pump out often seems to be at odds with the humility and simplicity of Christ: rather too much money lavished on TV screens and sound systems; perhaps it would be better spent on serving the poor. Yet this one didn’t seem especially prosperous, just large and energetic.

The preaching was good, Biblical, and honest. The worship was passionate. As a first-time visitor I was encouraged to stand and was warmly applauded by everyone. Outside, in the lobby, there is a bookshop and a free café serving iced coffee to anyone who wants it.

Yet here is the thing that struck me the most: the overwhelming evidence demonstrating that God is doing something remarkable in the world. The English-language congregation has an average of 1,500 attending every week. They also have a congregation for Bahasa Malay speakers. There is also one for Tamil-speaking Indians and Sri Lankans, another for Nepalis, and one for people from Myanmar. The Myanmar congregation meets at midnight. Most are restaurant workers, busy until the restaurants close at 11pm, at which point they head to church. Hundreds of them, every week.

After the service I met some of those attending: Malay Chinese, mostly first generation believers who have come to Christ in the last few years. I met an Iraqi Kurd, two Iranian couples, a family from southern India, an Indonesian student, a lady from Bangladesh, a group of Chinese students. People from all nations, tribes and tongues, coming together to worship God. The vision from Revelation is coming true in front of our eyes.

In all our talk about refugees and immigrants we focus on security, on national identity, and on the economics of immigration. We are missing the point. God is moving people around the world for his own purposes. Let us, as a church, not miss the opportunity to see Biblical prophecy fulfilled before our eyes.

Lahore, From Afar

The waiter brought the plates of food to our table, plonked them down, and walked away. We were in a French restaurant in a shopping mall in southern England. In an effort to replicate the French dining experience the restaurant had been decorated with old French film posters and tiled in black and white, and the bad service from surly staff added another layer of realism.

My son and I tucked in to massive dishes of mussels, since we were in the UK temporarily and were soon to be heading back to Pakistan where mussels are as rare as rude people. My wife had a steak sandwich. The other kids had asked for macaroni cheese, the kind of bland dish restaurants serve to children in an effort to keep them quiet. Outside, shoppers were dashing to and fro. A couple with a small child came and sat at the table next to ours and played with their smartphones until their child started screaming, at which point they gave a smartphone to him to keep him quiet. Our waiter came and dropped off a jug of tap water and seemed to think that he was doing us a personal favour by doing so.

Suddenly my wife’s phone bleeped. She checked it, looked at me, and said “Bomb in Lahore”.

The details were simple enough, containing the usual ingredients: a crowd of people in a city, a parked car, a network of people with murderous hearts. 8 dead, we were told.

Instantly my mind went back to Pakistan. I could imagine the crowded streets of Lahore, the throngs of people coming to see what was happening, the police shoving back the sightseers. The screams of the sirens carrying the injured to hospitals, the doctors and nurses rolling up their sleeves to perform their daily acts of heroism as they bandaged wounds and saved lives and informed grieving relatives that the man they sent to train as a policeman would not be returning home. I could imagine the screams of shock and the pain searing, agonisingly, into the hearts of people across the nation. I could imagine the cries of anguish from people across the country as they learned of a new outrage carried out by terrorists intent on destroying Pakistan.

Outside the restaurant the shoppers were dashing to and fro, bags of new possessions under their arms. My infant son spilled his water over himself. My daughter was ploughing steadily through her macaroni. My son was devouring his mussels. The people at the table next to us were eating in silence, eyes flicking to their phones every other bite. And far away, I thought I could hear the sirens.

How To Have a Good Religious Discussion

Technique B: Sincerity

The taxi pulled up outside our front door and the children and I piled in. We were going to school by cab as our own car was having one of its regular trips to the mechanic. The driver was a young man, perhaps in his mid-twenties, with gentle eyes and a luxuriant beard. He watched as the children misted the windows with their breath and drew pictures in it.

“Praise God, your children are wonderful” he said kindly. He enquired where we were from and expressed surprise at our Urdu.

“I can’t believe you would come to live in Pakistan” he said in amazement. I told him that I loved Pakistan and felt very privileged to live there, which made him smile with gratitude.

We spoke about faith. Most conversations in Pakistan head in this direction sooner or later. I told him that I followed Jesus and he nodded with pleasure and admiration. He loved Jesus too, he said.

He said that he drove the taxi only in the mornings, since he had a full-time job which started later in the day, but since he always went to the mosque for the first prayer of the day he had several hours to fill and would rather spend it working than sleeping. He was humble but devout. I liked him very much.

He wanted me to know more about Islam. It was not everything the media portrayed it to be, a point which I certainly agreed with. I should take the opportunity of being in Pakistan to learn more about it.

He was happy to listen to me in return and seemed to appreciate discussion. Having dropped the kids at school we arrived back home and I found myself wishing that I had more time to spend chatting to him. We exchanged contact details and shook hands kindly.

As a Christian living in Pakistan I am regularly invited to convert to Islam. I have no problem with this in the slightest. Why should Muslims who feel strongly about their faith not invite me to be part of it? Surely this is part of religious freedom. And when the invitation is presented in such humble and sincere terms, by people who clearly take their faith seriously, it is much more appealing than when the topic is presented aggressively and arrogantly.

I imagine Muslims feel the same way about Christians…

How Not To Have a Religious Discussion

Technique A: Aggression

He recognised me straight away. As I walked into the photocopy shop he instantly saw that I was a foreigner and beckoned me over. Ignoring my enquiry about whether I could get some documents copied, he sent for chai.

“Ah, British!” he said, smiling to himself. “The British really messed up Pakistan, didn’t they?”.

I didn’t know what to say. It was partly true at least. It was also very un-Pakistani to begin with such hostility. His smile was thin and insincere.

“Are you a Christian? I see. Well, you ought to convert”.

I smiled and considered my response. Everyone in the shop was looking at us, eager to see where this would go. As I opened my mouth to give an answer he jumped straight in again.

“If you converted, you would be so successful in life. So wealthy, so happy, everything going right for you. Why don’t you think about it? All you have to do is recite the creed”.

This was odd, like an Islamic version of the Christian Prosperity Gospel. I opened my mouth to respond once more, but to no avail.

“Hold out your hand” he barked in command. Dumbly, I did so. He smiled again.

“Just as I thought” he said. “Your palm says that you are a good man. But you could be so much better if you turned to Islam. Why continue wasting your life?”.

I wanted to say something back, to engage in dialogue, but he clearly had no intention of letting me speak. He outlined in rapid-fire Urdu the benefits of conversion and the dangers of hellfire. It was not a conversation; it was a monologue, a verbal assault. Finally, with an abrupt gesture he cut it short and bid me farewell.

“Think about it, won’t you?” he said, his eyes glinting.

The whole experience felt hostile. Oddly, I felt as though I were a schoolchild again and had been told off by the Principal, subjected to a verbal grilling about my failings in life and how I might improve. The man was not interested in dialogue, only in knocking down my beliefs. Frankly I failed to see how this approach could conceivably lead anyone to a greater interest in Islam; it only succeeded in making me feel small and foolish.

I then wondered how many Christians use this approach with non-Christians. It is so much easier to make speeches, to engage in monologue rather than dialogue! No tricky responses, no difficult questions to answer, just empty air to fill with arguments. It is easy. It is also pointless.

If I Ever Had To Leave Pakistan

Near our house is the visa office for most Western countries. Anyone living in Pakistan who needs a visa for the UK, Ireland, the Netherlands, Australia or a range of other destinations makes a pilgrimage here, armed with application forms, documents, flight bookings, and a face of grim determination. Every morning I see them queueing up, hopeful and perhaps just a touch desperate. They are eager to leave. Many people are.

One of the many contradictions of which the nation of Pakistan is constructed is that people here feel both a fierce sense of national pride and a strong tendency towards self-criticism. Many Pakistanis love Pakistan deeply and proudly, and yet criticise it without hesitation. Many would leave, given the chance. Many have already left, setting up colonies in Toronto and New York, London and Birmingham and Melbourne. Even the fundamentalists who scream hatred of the USA would give their right arm for a chance to live there.

We have done the opposite, moving from the West to live in Pakistan, and everyone thinks we’re insane. At first I did too, wondering exactly why it was that we had chosen to swap reliable electricity and sensible governance for the myriad eccentricities (if I’m being kind) and baffling illogicalities (if I’m not) of the Land of the Pure. The electricity comes and goes. Corruption is rampant. The police can’t be trusted. It’s hot and dusty half the year, cold and dusty the other half, and everyone stares at me whenever I walk outside.

Yet it would break my heart to leave. Why? What would I miss? The straightforward kindness of the people, for one thing, who have every reason to resent a British man and yet never seem to do so. The kindness and generosity of Muslim people. The smell of rain on dusty ground. The epic monsoon thunderstorms which split the sky asunder with a terrifying roar. The mountains of the north. The chance, the wonderful chance, to do something positive in a place of need, to praise Pakistan, to honour its people, to promote education, to bring peace between Muslim and Christian in a time of great fear and mistrust. The opportunity to see God move in the lives of others, to see him mould and change and refine us, to experience his love precisely when we most need it.

I do not want to leave, not yet. There is so much good here, so much beauty, and we are almost uniquely privileged to witness it when so few Westerners ever come here. I love Pakistan very much. I rather suspect I always will.

Advent in Pakistan

When I was a child the season of Advent seemed magical to me. A time of anticipation, largely of the food and presents that would come my way when the Advent candle finally burned down to 25. A time of joyous expectation. It tied in with the decorations in the town centre, with the Christmas music on the radio, with all of the trappings of Christmas in a Western country.

The older I became, the more the glitter and magic of Advent wore off. As I thought about the birth of Jesus it struck me that this was a rescue mission, a final and stunning act of lavish and proactive generosity on the part of a God who could not bear to be separated from his people. My rejoicing was replaced with wonder as I realised just how much humanity needed God, just how much God longed to be reunited with humanity, just how extreme and astonishing the rescue mission was.

And now in Pakistan Advent seems more miraculous, more bizarre, more incredible than ever. Most people here simply cannot believe that God would stoop to enter the world as a human: it would be beneath him, unworthy of his majesty. I can understand the objection. The incarnation of God in the person of Jesus Christ is a phenomenon not seen in any other religion, at any other time, anywhere else in the world. How could a divinity lower himself to such a level? It is unthinkable that God would require food, would stub his toe, would cry. I understand the objection, though I do not agree with it. The aspect of God’s nature which makes the incarnation possible is the unthinkable depth and breadth of his love. He would do anything, anything, to be with his children. What father would do less?

Apart from Pakistani Christians, nobody here marks Christmas. Save for the gaudily-decorated lobbies of the expensive Western hotels there are no decorations, no Christmas songs, no Christmas adverts on TV. We celebrate it quietly. I enjoy this very much. It is in keeping with the season of Advent: a secret rescue mission, a tiny baby delivered in a humble room in an irrelevant backwater of the Roman Empire, welcomed by lowly shepherds. The baby who would go on to turn the world upside down after three decades in isolation. Jesus, the ultimate sleeper cell. Not many here know of him, but he is there, and his love is as broad and deep as it ever was.